Thanasis Triaridis

There is only one Greek author who impresses me so much with his writings and his speech: Thanasis Triaridis, the most generous, tireless, unique person of our time. A Renaissance spirit of incomparable education, who generously offers all his works on the internet.

Giannis Farsaris - Author

----------

Thanassis Triaridis is a creator who cannot be satisfied by or, rather, constrained to a single literary genre. Over the years, he has engaged in writing novels, novellas, short stories, poetry, theatre, essays... Classifying him is difficult, both because he has provided exceptional works in every field and because he himself seems unwilling to fully conform to the conventions of any particular type of discourse. His theatre “calls for” one or two - at the most - characters on stage. His prose often adopts a fragmentary, but fully cohesive form.

His poems oscillate between a deeply personal tone and fierce denunciation. The only consistent characteristics underlying his works are his unrestrained imagination and his political thinking. Triaridis craves to speak, he does have things to say. And so, this multitude of heterogeneous elements ultimately defines a continuum, mainly because, above all, it is governed by and expresses his deep love for everything human, for humanity itself. This is what makes him not only a beloved creator but also an equally beloved person for those who are fortunate enough to know him personally.

Rosalie Sinopoulou - PhD in Comparative literature and drama studies - translator

----------

With great pleasure, we welcome to the radio technis one of the most significant contemporary Greek authors, Thanasis Triaridis. The occasion for getting to know him, among other things, was the three theatrical performances currently playing in Athens, all written with his masterful pen.

These include Dostoevsky's 'Crime and Punishment' at the Poreia Theater, directed by Dimitris Tarloou, 'Mengele' at the Nous Theater, directed by Anastasia Koumidou, and 'Mute Bell' at the Bellos Theater, directed by Marios Kritikopoulos and Panos Apostolopoulos. All three performances feature exceptional casts."

Studying Thanasis Triaridis' works, freely available online, it's evident that the cornerstone of his thinking is humanism. His texts are often provocative, heretical, extreme, boundless, yet written in an intricate and captivating manner. This creates intense literary magic, engaging the reader and making them feel part of the creation. Thus, Triaridis' literary discourse liberates because the reader can channel through it the unburnt emotions of life, something only great literature can achieve.

The majority of his writings (essays, poetry, prose) construct a unique dramatic universe that constantly surpasses boundaries, touching on major themes of human existence: love, man's murderous tendencies, Nazism, mutual death as a means of unity, the refugee crisis, and numerous other social issues.

Numerous critiques have been written about his work. Some come from extreme religious or political circles that ostracize him, while many literary figures, critics, and academics praise him for his authentic, creative, and contemporary narrative style that has breathed new life into Greek literature, with high originality and the peculiar magical realism of his texts.

His works are written in such a way that at their core lies a continuous effort to shake and shift the reader/viewer towards a more humanitarian reflection and social sensitivity. Triaridis knows that this is particularly challenging, thus intentionally or unintentionally imbuing his literary discourse with a unique and intense charm.

Having known him, I understand that he is a unique personality, a fiery intellectual workshop of thought and perception, with incredible analytical and synthetic abilities, navigating within an unbounded sea of sensitivity, emotion, and humanity.

Lambros Mitropoulos

----------

Lambros Mitropoulos.: Thanasis, welcome to the Radio Technis. It's a great pleasure to have you with us.

Thanasis Triaridis.: It's a great pleasure for me too, Lampros. A very high-quality work is being done at the Art Radio, and it's a struggle for rearguards in a society of mediocrity to seek cultural depth, which requires time and effort to achieve, while we live in an era where everything must be easy to consume.

L.M.: Yes, it's a difficult endeavor, but even if our work touches one person, it's important to us.

T.T.: I completely agree.

L.M.: The main reason for this discussion is your significant presence in Greek literature. Let's talk about the masterpiece adaptation you did of Fyodor Dostoevsky's "Crime and Punishment," which is currently being performed at the Poreia Theater. How did this adaptation come about?

T.T.: I am someone who places Dostoevsky at the center of his world. For me, Dostoevsky is the greatest author of the human condition. Before I was approached by the Poreia Theater to do "Crime and Punishment," I had written at least eight plays based on "Crime and Punishment," which, in my opinion, is the most significant novel of all times and all ages. So, I've been working on "Crime and Punishment" since I was fifteen, and at the age of fifty-two, decided to write a theatrical adaptation. But another theatrical adaptation of "Crime and Punishment" is "The Mengele," which is one of my most well-known works.

L.M.: What does "Crime and Punishment" address?

T.T.: It addresses the issue of moral murder. To what extent can a person kill to make the world better? This question, this magnitude posed by Dostoevsky with Raskolnikov, is in my opinion the paramount ethical issue of our civilization. If we answer this question, we are obliged to take a political stance for the whole world. That is, if you can kill with an axe a bad person, a person you feel is evil, who is a scourge to society, to humanity, then you have answered all the historical political questions of humanity.

L.M.: Throughout human history, we've seen that an ideological core can lead in this direction.

T.T.: Exactly. Hitler committed the Holocaust because he believed it would improve the world. And that's why in my work, Raskolnikov never speaks a word from Dostoevsky's book. He speaks words of Hitler and Christ. That is, Dostoevsky's entire role is made up of a pastiche of words and speeches of Hitler and Christ. To show what? That when you decide you have the right to do something to fix the world, you're entering the deepest core of fascism.

L.M.: You wrote somewhere that after January 27th, 1945, Dostoevsky became humanity's black box. How do you justify this?

T.T.: Yes, look, when Dostoevsky wrote "Crime and Punishment," the world read it as an exciting detective novel, slightly extreme and provocative. Why? Because for his time, Dostoevsky subjectivized the view of murder from the murderer's side. That is, we see the murder through the eyes of the murderer, the preparation for the crime, and the act itself. At that time, this was unimaginable. Today, because of Dostoevsky, it's absolute normalcy. In films, in novels, in narratives, in intense theatrical works. But back then, it was something unique. It was considered a provocative detective novel, "Crime and Punishment" and Dostoevsky was seen as a provocative, ingenious writer, extreme and slightly uncontrollable.

When Dostoevsky died in 1881, he was considered a great Russian writer, and twenty years later, he was seen as a great European writer. By 1930, he was regarded as the greatest Russian writer. In fact, he was considered even greater than Tolstoy by some. He reached the same level as Dickens, Balzac, and some even considered him better. Then came 1945. In 1945, on January 27th, Russian tanks entered Auschwitz. They saw what happened in the Holocaust. They saw the gas chambers, the crematoria, the skeletal figures, the children in Mengele's twin laboratory, and suddenly realized that what could only be described in the darkest imagination had come true. The absolute evil, not the outburst of brutality of an uncivilized people, but in the heart of a rational world, in the homeland of Kant, Bach, Beethoven, Goethe, and Schiller, with the tolerance of all of Europe, the Holocaust happened.

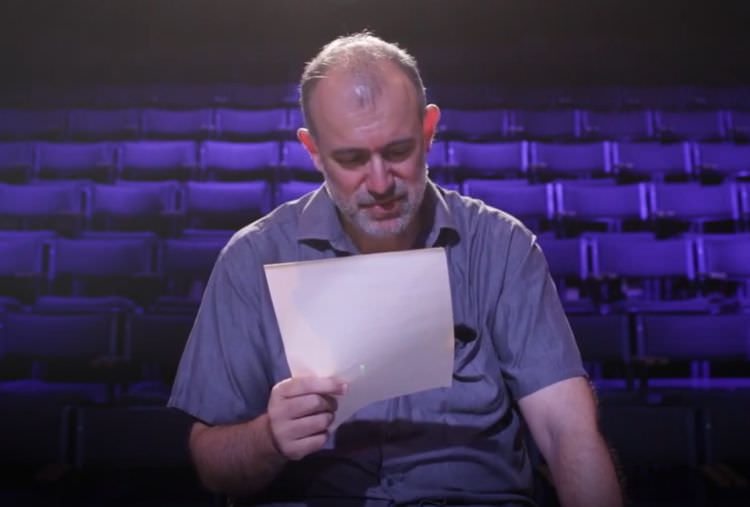

Photo from the theatrical performance "Crime and Punishment" currently being performed at the Poreia Theater adapted by Thanasis Triaridis.

L.M.: It's horrifying. What happened was the greatest shame of humanity up to that point. I will never forget what I read, that the Nazis tested the effectiveness of Cyclone B gas (cyanide) on 600 prisoners in Auschwitz, all of whom died within 20 minutes, and then it became the permanent method of execution for the prisoners.

T.T.: It truly surpasses human comprehension. Humanity found itself in terrible difficulty, what will I do with this? How will I manage it? Adorno said that nothing could exist after Auschwitz. Neither poetry, nor literature, nor art, since Auschwitz happened, the world stops. There is no civilization. Kantian theory that the world will progress is thrown aside. And at that moment, humanity said, where will I find support? The Gospels didn't provide it. The Quran even less so. At that moment, it reached out to the library and pulled out Dostoevsky.

And suddenly it saw that Dostoevsky was talking about January 27th, 1945. Suddenly, Dostoevsky, after the Holocaust, didn't just become a great classical writer. He became the author who addressed the stakes of the Holocaust and Hiroshima. Six months later, we have a plane that presses a button and erases a city. And another presses another button and erases another city. Humanity had to find something to hold onto, to see how it would deal with it morally, spiritually, and we turned to Dostoevsky. Who is the greatest of all, there is no other writer like him.

L.M.: The big question that arises is whether, after committing crimes, humans gain awareness? Because if we look at history, humanity progresses by sowing hordes of corpses.

T.T.: Here begins a discussion that I've been having in my books for the last 20-25 years. Man is born as a human, the human species is born through the genealogical act of murder. Murder is at the root of the transformation of the ape into a human. The ape becomes human when it uses a weapon of war. I'm not saying this, Walter Burkert says it in "Homo Necans". The famous book where man is a murderer. This is what Stanley Kubrick says in the opening scene of "2001: A Space Odyssey".

The Odyssey of Space, where two groups of humanoid apes fight and one takes a thigh bone from a skeleton and uses it as a weapon to smash the other's head, murder is the quintessentially human act. Man becomes man when he creates tools for murder. Burkert tells us that tragedy is a ritual of atonement for this genealogical murder of man. Therefore, the human species is a species that becomes human by murdering, and because it creates a cognitive and hedonistic sequence of thoughts, it begins and slowly creates culture. At some point, it attempts with this culture to control the violence of the species.

L.M.: Yes, of course. This was and is the great effort of the West towards civilization through constant contradictions and retreats.

T.T.: Yes, upon which Dostoevsky gives the central diamond of human reflection. And Homer talks about the violence of man, and tragedy discusses the violence of man, and Macbeth discusses the violence of man. But Dostoevsky comes in the midst of this intellectual journey to tell us, this is who we are. We are in this cycle. And he raises the issue of moral murder, which concerns humanity greatly.

Photo from the theatrical performance 'Mengele' currently being staged at the Nus Theater, written by Thanasis Triaridis. The play attempts to confront the most incomprehensible bestiality in Western history: the experiments laboratory of Josef Mengele in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

L.M.: The truth is that the world is improving, man has managed to a significant extent through culture to dominate his murderous nature.

T.T.: Yes, in the 1800s Kant told us that the world would take two steps forward, one step back. But progress is the destiny of the human species. Immanuel Kant came as the culmination of the Enlightenment and in a way reassured us. He told us that the world would gradually become better. And it is true that the 19th and 20th centuries nurtured Kantian optimism. Women found rights, at least in the Western world, democracy expanded, literacy expanded, today more people have better access to basic human goods.

So the world is becoming a little better. It still has inequalities, it still has setbacks, but it is getting a little better. The 20th century was a century in which man acquired technological power. Immediately he built Auschwitz and Hiroshima. This shocked us as humanity, it set us back. Man faltered, until the explosion of technology in the 21st century comes and shows that man has essentially activated a mechanism of self-destruction, whether it is ecological destruction or destruction through artificial intelligence.

L.M.: The issue of artificial intelligence is enormous. I imagine you'll deal with it in your upcoming books.

T.T.: Certainly in my next work. "Crime and Punishment" is the first of a trilogy drawing from Dostoevsky's "Crime and Punishment," the next work being "Frankenstein 3.R," which has been released, is available online, and will also be released as a book. The third book, currently in the writing stage, is "The Hunchback of Paris." These are three foundational novels of the 19th century, "Crime and Punishment," "The Hunchback of Notre-Dame," and Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein."

They are the three foundational novels that I adapt into contemporary dilemmas and the modern world. Hence, "Crime and Punishment" includes holocaust, Nietzsche, and the theory of the Übermensch, as well as Freud and psychoanalysis, as in the end, the protagonist kills his mother. His mother, Pulcheria, who exists in Dostoevsky's book for the first 100 pages and then disappears, in my work becomes the woman who provides redemption.

She says, "I am Alyona Ivanovna, come kill me." He kills her, and this becomes the punishment in my adaptation. Just as this happens in "Crime and Punishment," in "Frankenstein 3.R," set in 2038 to 2040, the new creature created is not the grotesque creature with stitches, but now something else. It is HOMO DEUS, the human-god, a creation of artificial intelligence made from human and adaptive electronic neurons, possessing a thousand times human intelligence, capable of picking up a mobile phone and annihilating a city, hacking the computers of secret services, and ordering the destruction of Paris. And it does this as soon as it is created. It becomes the destroyer of the world.

L.M.: It's a huge and very serious discussion about whether the decoding of the genetic code and brain structure with the help of biotechnology and artificial intelligence will lead human intelligence to lose its power and for power and authority to pass to supercomputers with immense data processing capabilities. I don't know if we could avoid reaching self-destruction; let's hope this doesn't happen.

T.T.: There's no chance we won't get there. Yuval Noah Harari in his book "Homo Deus" says that humans will lose the game; there's no turning back. And we'll see what kind of life this life will be, essentially technologically constructed artificial intelligence. In other words, just as we managed to make glasses for shortsightedness, we also made life that will be immortal and artificially constructed. It already exists out there, and it will explode in the coming years, just like all inventions, technical innovations, and technological breakthroughs. Man cannot easily control his kind.

L.M.: If these things happen as you describe, we are talking about dystopia, because love is one of the great pursuits, I don't think there will be a way for humans to be led to the search for love through all this abyss.

T.T.: There's no way. It's impossible. Man is an animal that hungers. That's what brought him out of caves, made him civilized, made him build civilizations, made him write the Iliad and the Odyssey, but it also made him create the atomic bomb. Man is a volitional being; he can't say, "How nice the wind is, whistling in the evening by the shore, so I'll live with it." We want everything. There's nothing we don't want.

We want to become immortal, become all-powerful, become omnipotent, become beautiful, travel everywhere. We want, we want, we want. We want to defeat diseases, we want us to bathe in a time of drought five times a day. If we could, we'd have private pools inside our houses. There's no chance of harnessing human desire through a moral order. And those who try, because indeed some people try not to waste water or try to recycle, not to use plastic, are minorities who eventually break down in insignificance, fueled by a conformism, essentially consumed by the monster of human greed.

Photo from the theatrical performance 'Lebensraum' that recently played in Thessaloniki, written by Thanasis Triaridis and will tour various cities in Greece. The theme it poses is how complicit the silent audience is in the crimes of humanity.

L.M.: I understand that, and I often think that in all this situation, we must counter with optimism and will.

T.T.: I try to counter with essentially the will, the will for humanist thought. That is, for me, all my writings carry in every way the anguish of forming within this terrible chaos a humanist thought. And to fight for this humanist thought to bring it forward again, because we have lost it. We have lost it long ago.

L.M.: But I believe that many writers do this, I think poetry does this too, not all writers, not all poetry, but I think this is an effort made by many people, isn't it?

T.T.: Yes, but unfortunately, there are many writers today who often accept, in order to justify the power that pays them, the inevitability of human brutality. You tell them, people are dying in Africa from hunger. Well, what can we do, that's human nature. You tell them, people are dying from pushbacks at sea. Well, what can we do, that's human nature. So they discover human nature when it comes to talking about the death of others. So, if you tell them, okay, since you had an illness, don't go to the doctor, don't have surgery, then they say no, I will do everything to live. I will do everything for myself. But I don't recognize in the person born in sub-Saharan Africa to do everything for himself.

L.M.: That, Thanasis, is a part of Western thought, as it has been cultivated and as it exists at the moment, but there is also strongly humanistic thought in the West.

T.T.: Yes, Western thought is not just one thing. Western thought has this rampant cynicism, but we must say that it also contains various seeds within it; it has Rousseau, it has Hugo, it has Giannis Agiannis. So I would say that there is a spiritual battle in my opinion, a literal battle, a war, between pragmatic cynicism and humanism. I prefer to be in humanism, and I admit that often I cannot serve it because it is very difficult to serve ideas.

L.M.: In the chaos and contradiction of the world, serving mainly humanitarian ideas is a great challenge and particularly difficult. But let's switch to poetry for a moment, which as you know is a central theme on Radio Art. I know that at some point you were shortlisted for the state poetry awards, you declined it, sent a letter to the Ministry of Culture, would you like to comment on why you declined?

T.T.: Look, there are two ways to reject a state award, a list, a shortlist, state awards. For me, both are equally strong within me. The first way is the notion of the award itself. How can I recognize in any person the right to stand on a pedestal, at a height higher than mine or anyone else's, and say, "We, the 9 of us, we, the 7 of us, we, the 129 of us, consider that Lampros is better than Thanasis, or Thanasis is better than Lampros"?

Where in literature, in art, in painting? In the sea of subjectivities? But what does "better" mean? Van Gogh died begging to sell paintings and couldn't. Throughout his life, Van Gogh sold a painting for five francs; that painting was sold because a passerby accidentally stepped on it and pitied Van Gogh, giving him five francs to take the painting. One hundred years later, that painting was sold at the Tate Gallery in London for five million francs. It was the sunflowers. So who is to say that X, Y, Z are great painters and that Van Gogh, sitting on the street corner, is insignificant? Who?

So, from where and why should I, who know the history of art well and know that Medea won third prize at the 429 BC Dionysia and there are two works that were above Medea but no one knows them today, accept that 7, 9, or 39 people have any greater value than what you, I, or anyone else says? Therefore, the concept of the award, which presupposes that I accept the superiority or authenticity of others' judgment in order to be awarded, does not cover me at all.

L.M.: I understand that, but many great poets you admire have been awarded and accepted state awards, such as Dimoula, Patrikios. Of course, Elytis, Seferis, who have been honored with Nobel Prizes, but there is also the case of the famous French writer Jean-Paul Sartre who refused the prize in 1963.

T.T.: I know, many of my friends have been awarded, although I appreciate many of the people who become members of the committees. I appreciate them a lot. But I do not accept from the outset of my reasoning that there is even one who is one thousandth superior to the other, so as to award him. That's one thing. The second is that the awards are of a state that, as part of its central policy, pushes back, for example, with the sinking of Andriana, 648 people died. From where and why should I be awarded, when my book was titled,

"The Sea Will Cleanse Us," spoke about those slaughtered and murdered at sea by state pushbacks? So think about the contradiction. Will the state come to award me for a book that speaks about the murdered? How much further illogical can it get? I wouldn't accept awards even if the Art Radio gave them. Which is neither a state nor kills people at sea. I wouldn't accept awards even if you were a member of the committee, which I greatly appreciate and your judgment is such. Why? Because I do not accept the concept of the award.

L.M.: But there are some well-intentioned people on the committees with honesty and great work.

T.T.: Yes, there are, they do it with good intention, they just can't make the abductions that I do. And I appreciate them and know some of them. That's why I said they couldn't have done it to offend me. My first thought was that, being such a lunatic as I am. But then the thought prevailed that people did it with good intention, just to the wrong person. It pacified me, so to speak.

L.M.: From what you said above, but mainly from your writings, a subject that has triggered your thoughts and particularly your poetry is refugees. Don't you think that there should be a fair distribution of refugees in Europe?

T.T.: Here you touch on the core of a major problem. A huge number of people on the planet are below the tolerable limit of poverty. Therefore, migration and refugees are not created by anything other than unimaginable miseries, unimaginably wretched living conditions. For someone to board a slave ship with his children, to risk dying to come here, to be pushed back, and yet to choose this over sitting there, means that there it is even more horrific. Life has a force. You go where you feel you have more opportunities. So either we kill them, as extreme conservative circles claim, or we should consider if we are interested in redesigning life, which means we will lose things ourselves to share with others.

L.M.: However, history shows that we are not solidarity beings in order to share our belongings.

T.T.: Exactly, so my proposal is indeed that. That if you have a European Union, which has 700 million people and is a continent that is aging, it must accept another 700 million, but primarily, it must spend money, create infrastructure. Europe, America, China, and the big multinational companies, which are entities in themselves, must create that infrastructure so that there is no extreme poverty that breeds overpopulation. That is, work must be done locally in poor countries. In sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia where your life is a constant despair, you give birth to 26 children without expecting anything at all. These people need to be given a perspective on their lives. Humanity at this moment is facing a huge ethical dilemma, which I believe it has answered in the worst ethical way.

Photo from the theatrical performance 'Mute Bell' written by Thanasis Triaridis, playing from Monday, April 1st, 2024, and every Monday and Tuesday at the Bellos Theater in Plaka. A story with majestic music turned upside down by the wind, nighttime despair, massacres and loves beyond love. In other words: a story about the blending of the innocent and the guilty.

L.M.: I don't know if Europe can absorb refugees as much as its population, but it can certainly absorb many, and local infrastructure must be created in poor countries. Do you believe that ethics is inherent to human nature or is it a luxury of the mind?

T.T.: The ethics upon which I base all my effort is not inherent to human nature. It is a mental luxury of humans. Well-fed people like you and me can have it; enlightenment created ethics. Ethics is not inherent to human nature but is conflict. Conflict and domination. And you understand that in any form of conflict, those who have technological superiority are the winners.

L.M.: You have written several poetic books, among which one was proposed for an award; do you consider yourself a poet?

T.T.: What I write are various stories expressed with lyrical language. Generally, I put the poems I write in quotation marks. Because I consider the concept of poetry very high. Time will tell if someone's effort is ultimately poetry.

L.M.: Are there any Greek poets you admire?

T.T.: There are significant poets; I loved Markos Meskos, Kiki Dimoula, and others. Recently, George Blanas passed away; in my opinion, he was a great poet, as was Titos Patrikios. Cavafy and Anagnostakis are great poets. Especially for Cavafy, I believe he is one of the greatest poets of humanity in the last three hundred years and indeed the only one in the history of literature where a regional language succeeded in creating a global work.

Usually, global works are created by metropolitan languages. In ancient Athens, the ancient Greek written by Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides was the language of the metropolis. In Rome, Virgil, Ovid, and in England, Shakespeare respectively. For the first time in the history of literature, we have a poet like Constantine Cavafy with a regional language becoming global. And he achieved this with 10,000 words, with those 286 poems, because there are 154 published poems, 75 unpublished ones, 27 disowned ones, and 30 incomplete ones.

L.M.: And what about art in our era when technology is developing at dizzying speeds?

T.T.: Today, art spreads in chaos in the same way that our lives do. Chaos is primarily what the terrifyingly rapid technological evolution creates, which human nature cannot assimilate. They say it takes three generations to assimilate an innovation, let's say the car. When the innovation of the car comes, the third generation incorporates it into its life. Or the airplane. The invention of the airplane comes, and the third generation now substantially incorporates the airplane into its life. Here we live in the following unimaginable.

I was born into a world where we wrote by hand and if we wanted to communicate with our loved ones, we would go to a queue or a kiosk or a telephone booth to make a call when we were abroad once in 10 days. Suddenly, somewhere in my 30 years, came the mobile phones. Before my generation could assimilate this development, the internet came, the Smartphone came, social media came, suddenly we mutated into a mature age within this reality. New generations use communication tools they found on their way and which we know will change in five years. Art stands helpless in front of this. And the same happened with cinema and television.

Today cinema is the primary art. Even on television, TV series are the great novels of today. The same happened with the novel. When the novel started, everyone thought that novels were a cheap thing. No one thought that Balzac would be a pillar of world culture. Because it took time for assimilation. Cervantes did not sign Don Quixote because he considered it a very vulgar thing. When he wrote Don Quixote, he did not understand that he was writing the major text of Western literature. So art today is in this chaos, in a continuous whirlwind that turns, and in this whirlwind, it must form its truth.

L.M.: For now, most artists follow traditional methods of publishing their works, but it's only a matter of time until they assimilate new technologies.

T.T.: Exactly, so what do we do? Do we say, "I will write a novel, I will write a play, I will write a poem"? Do we stick to the tried and tested methods of the past? We dare not explore what's happening in this mysterious world of participatory internet art. Why does it frighten us? Because we don't know it, because we say in five years it might change, whereas, let's say, the novel, the book, is something given. However, soon art will enter this realm.

I have written a book called "If you are, I am." It's a novella. In this book, there is an artist who lives in the 22nd century in 2110, let's say, who creates digital flowers and digital animals that grow within the digital world. She goes by the pseudonym Gloria Intera. And in a way, she creates this so-called evolving art. She creates art grams, like holograms, art grams. I don't know if this is the future of art. But in my opinion, very soon, art will assimilate technical progress and will give birth to new forms.

L.M.: You are one of the few Greeks who have made all your works available freely on the internet under this logic.

T.T.: This is a frightening potential that technical culture has given to modern man. The potential for self-publishing and self-expression. In the old days, to publish a poem, you had to pass through the judgment of literary magazine editors or publishers. Now you can self-publish your poem, your short film, your paintings, your photographs, even your novel, on the internet, without any intermediaries.

This is very good because essentially it gives everyone the opportunity for self-expression, and amid this chaos of creation, what stands out is what is more dynamic and can reach others. In this sense, when I understood what the internet was many years after its existence, I immediately said that all my books would be on the internet. And indeed, my publishers considered it unthinkable. And I lost many publishers like this. Some publishers said, "Are you crazy? Why should I pay to publish your book when someone else can find it with a click?"

L.M.: Many do this abroad basically; what has been your experience so far?

T.T.: Let me tell you what I experienced. I experienced an unprecedented freedom to write whatever I want. My book "Melenia Lemonia” was first released on the internet, it did very well, and then it was published as a book. I couldn't have published it in the traditional way. It's an extremely extreme, extremely provocative book. If I didn't have the prospect of publishing it on the internet, how would I have written it? To where would it reach? To whom? The internet gives you the opportunity for freedom.

L.M.: Of course, this presupposes that you have the ability to make a living from another source, as is the case with most authors.

T.T.: Right, as a writer, you can't make a living, in other words, very few writers achieve their livelihood from their work. Certainly, a writer like me, who is very provocative and extreme and on an expressive level, is not interested in marginal edges, I couldn't have made a living in the 60s or the 80s. So I'm lost either way. There are very few writers who are so successful with their work that they manage to live off their royalties in one way or another.

L.M.: Thanasis, our conversation has already become a river, flowing towards its end. What has life taught you so far, if you had to say it in a few words?

T.T.: On a political level, that all stakes are open, and people should strive to claim them. When we see injustice, we must act. When we see evil, we must not allow it. When we see a child dying of hunger, we must find a way to connect with them. That's on a political level. On a personal level, that people progress through their mistakes, and through these mistakes, we strive to love and be loved, to manage the great affair of love. I say it as I think it now.

L.M.: I borrow the poem VII 277 of the ancient poet Callimachus, "Who are you, stranger survivor? Leontichus found you on the shore and buried you in this grave; he wept for his uncertain life as he thought, for he too wanders the seas like the gulls. So, who are you, Thanasis?

T.T.: This masterpiece of a poem resonates with me greatly. Look, I am someone who would do exactly what Leontichus did in the poem of the same name. This is a poem where someone finds a survivor dead, a body washed ashore, doesn't know their name, and makes a grave for them. And in a way, he doesn't just make a grave for the dead, he makes a grave for himself too. He says, "This is how I will die, no one will find me, so on your body, which I don't know, I put my own name, Leontichus."

He knows that he too will die someday because he too travels the seas. So in a way, in this unthinkable thing, I have to say that I am someone who sheds tears for the corpse in front of him, for the lost person he finds in front of him, and tries to find his identity through him. In a way, I am someone who finds his identity in the defeated, the desperate, in those who hunger, in those who were massacred, in those who were killed, in all of them, whom I want to be close to in many ways.

L.M.: If I asked you to tell me, what words/concepts dominate your thoughts, what would you say?

T.T.: Of brotherhood, as the French Revolution puts it, I believe that out of liberty, equality, and brotherhood, the most important is brotherhood.

L.M.: Thanasis, we've reached the end, and I'd like to bid you farewell with an exceptional poem by Takis Papatsonis.

Our last day

If tomorrow, let's suppose, marks our last day,

(something beyond our control and not at all improbable)

in the county of life, what account will we render for the unspent

treasures, what for the indifferent disdain,

deficiencies in use, hesitations, and unforgivable neglect?

T.T.: It's wonderful, I hadn't thought of that. I have read Papatsonis. It's a very nice poem. I would also like to bid you farewell with a very beloved poem of mine by Manolis Anagnostakis.

The decision

Are you for or against?

Just answer with a yes or a no.

You have considered the problem

I believe it has certainly tormented you

Everything torments in life

Children, women, harmful insects, plants, lost hours

Difficult passions, broken teeth

A mediocre film. And this surely tormented you as well.

So speak responsibly.

Just with yes or no.

The decision is yours.

We're not asking you, of course, to cease

Your occupations, to end your life

Your favourite newspapers, your discussions

In the barbershop on Sundays, your times at the stadium.

Just one word. Go ahead:

Are you for or against?

Think it through. I'll wait.

L.M.: Thank you very much, Thanasis, for this exceptional conversation.

T.T.: I thank you, Lampros, for everything, and you understand, I hope, how important our meeting and the conversation we had are to me.

L.M.: And for me, it is important, and I hope this bottleneck with our conversation reaches the hands of someone, who perhaps it will entertain or console, as you say on your own website.

Selection of Poems

From the poetry collection "I will wait for you," poems 2013-2018

Brew

The image is well-known

(everyone has seen it):

Liberty leading the People

by Eugène Delacroix

(in the Louvre, yes, in the Louvre of course)

where the bare-breasted Liberty charges

towards the Future (with a capital F, don't be stingy)

and the others follow,

hot rifles, ready pistols, excellent swords,

naked swords waving like flames,

willful gazes, and shouts - yes, shouts -

of History.

And we all exclaim,

oh, what a bosom and what fervor –

and what magnificent History is this,

this is how Liberty should be:

theoretical and daring

filled with the milk of the Future,

if you like poetic descriptions

(and if you don't, it doesn't matter,

the world likes them...)

However, it is also known

(and this we have all seen -

or at least, we can all see)

that that Liberty and those with it

trample upon something, some corpses,

upon some former bad people,

upon Enemies, people with impure blood,

upon rubbish, mere brew of the Future...

(Don't be stingy, it told me,

every shout has its brew, that's how it goes…)

From the history of Petros Boles

They went, so to speak, to Petros Boles,

during a break from his work

(blood-filled, on a bench

resting a bit from beheading

with his tender knife),

stood against him the wise ones

(they had donned their crowns and rings

and all those things they wear when seeking the truth)

and asked him:

"Tell us, Petros Boles,

you who have seen so much,

do people have a soul that ascends to the heavens,

that lives eternally in the universe,

or not,

are they merely sacks that pile up,

and vanish into the abyss of nothingness?"

Petros Boles pondered a bit,

somewhat discomforted –

what did their wisdom have to do with him,

he was for other things...

Reluctantly and hastily he answered them:

"I know nothing of what you say –

I only know that s k u l l s s m e l l ..."

And immediately he rose holding

his knife, to begin again.

I'll wait for you

When I die

friends who want to remember me

wake up at night

and search your phones to see if it's raining in Addis Ababa,

if the orphanage in Tesfa is flooded with mud,

if the thunderstorm rattling on the tin

disturbs the children's sleep.

In this search

(and not in books or texts or words)

my memory will nest.

There I will be,

in the touch of your finger on your touch screen,

and I'll wait for you to dawn

to tell me the tin roof endured,

that the children woke up well.

From the poetry collection "The sea will wash us away," poems 2018-2020

A ship once without any flag

A ship once traversed the world

And became a dark legend amidst the oceans,

And one day it vanished, like all ships do,

But it haunted forever the times of mankind.

No one ever learned who the sailors were

Or who the captain was, or if there even was one,

With whom it sailed, who read the maps,

Where its compasses pointed, toward which meridian?

The only thing everyone knew was the History,

That the ship resembled a fearsome monster,

That it crushed every boat that came near,

That it sowed destruction everywhere, blood and slaughter.

Only an old blind man in a port

Said that nothing ever deserved them.

The only thing that made them that ship:

That it never raised a flag high.

They killed him – what was he? A blind beggar,

A dirty drunkard, a pitiful liar...

To say that they were the black murderers,

With their bright flags constantly shining?

And so no one remained to speak of the ship

That its mast remained forever empty,

Because the sailors knew that if they raised a flag

They would become butchers in some army.

A ship once without any flag

Sailed free amidst the oceans,

They crushed it, they sank it, like all ships do,

But it haunted forever the times of mankind.

In Italy that you loved so much

And as Cavafy told us,

The only thing that remains is memory,

Not the memory of a photograph,

But that of the inner, tremendous moment

That will be lost forever with you,

A moment, however,

Where you feared death a little less

In the Boboli Gardens of Florence,

In Italy that you loved so much,

That summer afternoon by Lake Izzoloto

When a light warm breeze blew

And the boy said to the girl

"Think about how many have passed through here where we stand...",

And the girl answered him

"But now I don't see anyone around us,

So even if we die tomorrow

We can say that there was a time

When Lake Izzoloto belonged only to us".

Shortly after, the whistles from the guards were heard,

A sign that the visit to the Gardens was over

And the visitors had to leave.

The sea will wash us away

"The sea will wash us away,"

You said that morning and I knew

It was a figure of speech, a poetic rhetoric,

As I had read so many books, so many wise men

Who said that people are not washed away

And not reborn, only submerged in decay,

And yet I liked your conversation, perhaps because

It was early and the air smelled of autumn's suspicion

And moreover while you said it

You looked so deeply into the horizon

That this phrase seemed like a complement

To your majestic figure,

Like a verse from an exquisite poem that will never be written,

And with poetry, as is known, something magical happens,

It can rhetorically persuade

To tell you lies to your face

And you accept them as ornaments of the morning beauty.

But now that much time has passed

I consider your former phrase differently

Since it's no longer morning

And no suspicion sharpens the air,

And you're gone forever

So without your gaze the horizon will remain empty

And all certainties will gradually crumble,

So I desperately seek a sign,

A small sign,

That might leave a possibility open

For the wise men and all the books to be wrong,

That might leave a possibility open

In the end indeed

For the sea to wash us away.

From the poetry collection "For the unknown slaughtered"

The most terrifying

The most terrifying thing about people

is not that they give birth to murderers,

butchers, strategists, executioner soldiers,

bombing pilots,

gas chamber wardens,

men who entered the enemy's city

and melted the heads of infants against the wall.

The most terrifying thing is that we got used to

the statues of butcher strategists,

the parades of murdering soldiers,

the celebrations that call heroes

those who melted the heads of infants against the wall.

The most terrifying thing is that we got used to

you and me.

The cliff flower

At the edge of sheer cliffs blooms a flower,

unrivaled in beauty, enviable in appearance,

they call it the cliff flower, the song of mourning,

and it's a terrible curse and a murderous bloom.

Just seeing it is enough to make the world disappear,

and to plunge immediately into the black void.

But even if only your mind imagines it

for sure you'll get lost in the lament of madness.

But it stands on the cliff and will wait for you,

and it's a gift for you, waiting there.

Because the elders say who know the world:

without the cliff flower life is dead.

The glory of men

You know, there has always been a suspicion

and now it clears slowly within me

that the greatest glory

is all that we have lost

while reaching out our hands to touch them:

The trains that departed from the station

a breath before we could climb aboard,

the sunsets that faded

before we could stand before them,

the people we stepped towards to reach

but turned the corner and were lost in the crowd.

This is our glory,

the glory of men,

to remain stranded on empty docks

seeking the lost trains,

the lost evenings,

the lost people,

that encounter you know you'll never achieve

but you'll always strive to touch it,

again and again,

until the end.

Brief Biography

Thanasis Triaridis was born in 1970 in Thessaloniki and studied Law at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

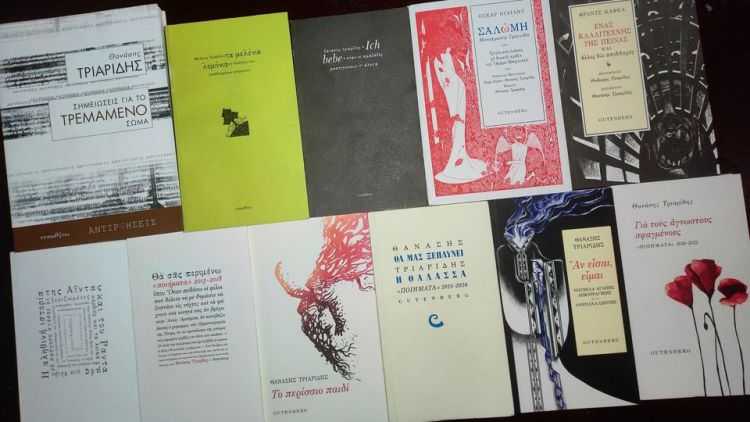

Since 2000, he has published 60 books, including novels such as "The wind whistles the dome," "Melenia Lemonia," "Green diamonds," and poetry books like "I will wait for you", " The sea will wash us away", "For the unknown slaughtered," and fairy tales such as "I dreamed of white christmas", "The excessive child," etc.

For years, he has been organizing seminars on various aspects of western culture as well as workshops on triggering theatrical writing.

All of his books and theatrical works are freely available in the Open Library (www.openbook.gr/tag/thanasis-triaridis/).

He has published (in print or electronically) 30 theatrical works, including "Mengele," "Oidipous," "Lebensraum," the trilogy "Leopold, Football, HIV," "The Laundry," "The Hood," "Frankenstein 3.R," among others. More than 60 performances based on these works have been staged in Athens and other cities in Greece, Germany, the USA, Cyprus, and online

His works have been translated into English, French, and German.